The NASA Ten Rules of Programming

My interpretation of these rules with Golang examples.

NASA did not write these rules to win arguments on the internet. They wrote them because software failed in ways that were expensive frightening and sometimes irreversible.

The rules are short. Almost annoyingly so. That is intentional.

Each rule is a reminder that complexity is not free and that computers are fast but humans are fragile.

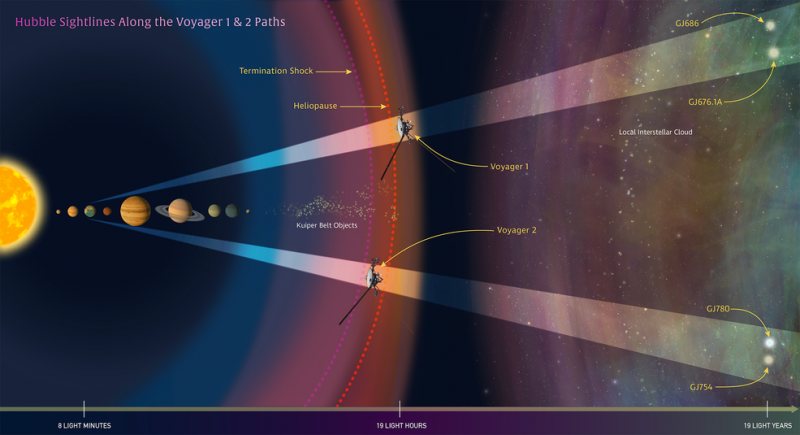

They helped put flying metals in orbit and manage Voyager 1, the most distant human made object.

Let’s walk through all ten using Go not because Go is perfect but because it makes these ideas painfully obvious.

Rule 1

Restrict all code to very simple control flow

If your logic requires a mental stack trace to understand it will fail at the worst possible moment.

Go helps here by being boring on purpose.

Bad

func process(x int) int {

if x > 0 {

for x < 100 {

if x%2 == 0 {

if x%3 == 0 {

x += 7

} else {

x += 3

}

} else {

break

}

}

}

return x

}

Good

func process(x int) int {

if x <= 0 {

return x

}

for x < 100 {

if x%2 != 0 {

return x

}

x = nextValue(x)

}

return x

}

func nextValue(x int) int {

if x%3 == 0 {

return x + 7

}

return x + 3

}

Simple flow is not about fewer lines. It is about fewer thoughts.

Rule 2

Give all loops a fixed upper bound

Unbounded loops are promises you cannot keep.

They say trust me this will eventually stop. NASA does not trust that. Neither should you.

Bad

for {

data := read()

if data == nil {

break

}

process(data)

}

Better

for i := 0; i < maxReads; i++ {

data := read()

if data == nil {

return

}

process(data)

}

Even when reading streams you can still impose limits. Timeouts retries counters budgets.

Infinite loops belong in theory not production.

Rule 3

Avoid heap memory allocation after initialization

This rule scares people because it sounds extreme.

What it really says is do not allocate memory unpredictably while running critical logic.

In Go you do not control the heap but you can control when and how you allocate.

Bad

func handle(req Request) {

buf := make([]byte, req.Size)

process(buf)

}

Better

type Handler struct {

buf []byte

}

func NewHandler(maxSize int) *Handler {

return &Handler{

buf: make([]byte, maxSize),

}

}

func (h *Handler) Handle(req Request) {

process(h.buf[:req.Size])

}

This is not about micro optimization. It is about predictability.

The garbage collector is helpful. It is not magic.

Rule 4

Restrict functions to a single purpose

If a function does more than one thing it lies about its name.

Bad

func SaveUser(u User) error {

validate(u)

db.Save(u)

log.Printf("saved user %s", u.ID)

sendEmail(u)

return nil

}

Better

func SaveUser(u User) error {

if err := validate(u); err != nil {

return err

}

return db.Save(u)

}

Side effects should be explicit and separate.

Small functions fail smaller.

Rule 5

Use a minimum of two runtime assertions per function

This rule is about defending assumptions.

In Go assertions usually look like early checks.

Bad

func divide(a b int) int {

return a / b

}

Better

func divide(a b int) (int error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0 errors.New("division by zero")

}

return a / b nil

}

Assertions are kindness to future readers. Especially future you at 2am.

Rule 6

Declare data objects at the smallest possible scope

The longer a variable lives the more places it can hurt you.

Bad

var result int

func compute(a b int) int {

result = a + b

return result

}

Better

func compute(a b int) int {

result := a + b

return result

}

Short lifetimes mean fewer ghosts in the system.

Rule 7

Check the return value of all non void functions

This is the rule Go takes personally.

Ignoring errors is lying to yourself.

Bad

file _ := os.Open("data.txt")

Better

file err := os.Open("data.txt")

if err != nil {

return err

}

Errors are information. Discarding them does not make them go away.

Rule 8

Limit pointer use

Pointers increase the number of possible states your program can be in.

Go uses pointers but discourages pointer gymnastics.

Bad

func update(u *User) {

u.Name = strings.ToUpper(u.Name)

}

Better

func update(u User) User {

u.Name = strings.ToUpper(u.Name)

return u

}

Use pointers when you must not because you can.

Rule 9

Compile with all warnings enabled and treat them as errors

Go does not have warnings. It simply refuses to compile nonsense.

Unused variables unused imports unreachable code. All dead on arrival.

That is a feature not a limitation.

If your language allows warnings treat them like failures. Your future stability depends on it.

Rule 10

Use static analysis tools

Humans miss patterns. Machines do not get tired.

In Go this means tools like

- go vet

- staticcheck

- race detector

Example

go test -race ./...

These tools are not optional extras. They are part of the engineering system.

NASA trusted them with spacecraft. You can trust them with your backend.

The quiet lesson behind the rules

The NASA rules are not about cleverness. They are about humility.

They assume that you will forget. That you will misread. That you will be interrupted.

They are written for humans under pressure.

Go as a language aligns with this philosophy almost accidentally. Simple syntax explicit errors limited abstraction boring defaults.

The rules remind us that reliability is not achieved by brilliance. It is achieved by restraint.

And restraint scales better than genius ever will.